In supply chain, specifically freight, profitability is often determined by how efficiently cargo is moved. Due to rate volatility, cargo space, vessel or aircraft availability, under- and overutilization often impacts the bottom line. Oftentimes carriers or shipowners penalize this through a dead freight clause.

Dead Freight is the compensation that a shipper or charterer pays to the carrier or shipowner for not fully utilizing the agreed cargo space on a vessel or aircraft. Dead Freight is often found in charter parties and liner terms to protect the shipowner for reserving a vessel, equipment or cargo space.

To understand the dynamics of dead freight, it’s important to take a closer look at the role of the shipper or charterer (the party who charts a vessel or books vessel space) and the carrier or shipowner (the party who supplies the vessel or vessel space).

Both parties will typically formalize and sign a service or charter agreement (also known as a charter party), that binds both parties to their responsibilities.

Oftentimes, a dead freight clause is included into the terms and conditions of service contracts or charter agreements, so that the carrier or shipowner is able to recover lost revenue due to the inability of the shipper to fulfill the agreed cargo load or to fully utilize the reserved vessel space.

How Does Dead Freight Occur?

In a perfect scenario, a shipper or charterer is able to fully utilize the cargo space, vessel or aircraft that was agreed to in the terms of the charter party or service agreement.

However, there can be several reasons why a shipper is not able to fully utilize the cargo space, ranging from production issues to disputes with the buyer or consignee. Let’s take a closer look at the main reasons why dead freight occurs.

- Cargo Not Available – Closer to the agreed loading date, the shipper may encounter production issues or order amendments resulting in the non-availability of certain cargo for the intended departure.

- Insufficient Loading Time – In a charter party, the loading time is clearly specified. In certain circumstances where loading time extensions are not granted, the vessel may need to be unberth and would depart with dead freight.

- Cargo Damaged – During production or transport, cargo may get damaged, failing to meet the required quality for shipping. This scenario may also cause dead freight.

- Incorrect Loading Equipment – The port at origin may also be unable to load all the cargo due to insufficient or lack of proper loading equipment.

- Dispute Between Buyer and Seller – If there are disputes between the seller and the buyer, the seller or shipper may not be able to ship the entire cargoes per the stowage plan. This may result in underutilization of cargo space, which may ultimately be counted as dead freight.

- Non-Fulfillment (MQC) – Carriers and beneficial cargo owners (often shippers) sign a service contract for a Minimum Quantity Commitment (MQC). This is the minimum quality that the shipper will agree to ship. In the event where this minimum volume threshold cannot be met, the carrier may regard the unutilized volume as dead freight.

How Is Dead Freight Charged?

There are several ways to calculate dead freight and the amount, as well as the method depending on the type of freight and the carrier or shipowner.

Containerized Cargo

For containerized cargo, the calculation is rather simple. Carriers typically calculate the dead freight as the minimum quantity commitment minus actual consumption (also known as the total shipping volume).

Break Bulk & Charters

For bulk shipments, the calculation is slightly different. As cargo isn’t containerized, shipowners generally add terms and conditions to a charter party stating that dead freight is incurred when there is a difference in the volume of the cargo agreed upon vs actual load of the cargo.

How Does A Dead Freight Clause Look Like?

Depending on the type of charity party the shipowner may opt to include a dead freight clause that protects them from underutilized cargo loads or shipping volume. Below, you’ll find an example of what a dead freight clause looks like:

DEAD FREIGHT: The shipper shall declare a stowage plan before the arrival of the chartered vessel at the port of loading. The shipper should load the declared quantity reflected in the stowage plan. In the event that the shipper is unable to load the declared quantity communicated in the stowage plan (short shipped), the shipper or the consignee shall pay dead freight.

Dead Freight Case Study

Let’s explore the concept of dead freight with a break bulk shipment as an example. In this case study, a buyer in Japan has agreed to purchase 5,000 metric tons of fertilizer from a supplier in China.

The buyer and seller have agreed that the buyer will arrange transport to the final delivery location in Japan. Therefore, the seller (who is also the shipper) is chartering a vessel from a shipowner.

The shipper and shipowner have agreed to the liner term Free In/Out Trimmed (FIOT), which indicates that the cargo owner is responsible for loading, unloading, and trimming of cargo.

In the charter party (between the shipper and the shipowner) the shipowner has agreed to provide a vessel for the shipment of 5,000 metric tons from China to Japan with a specific loading date from March 1 to March 7, 2022. The charter agreement also indicates a dead freight clause.

During a quality assessment, the shipper has realized that 25% of the fertilizer does not meet the required quality standards and is therefore unable to ship them.

In light of this, the shipowner exercises their right to claim compensation for the 25% underutilized cargo usage under the dead freight clause of the charter party. Therefore, the shipper must compensate the shipowner appropriately.

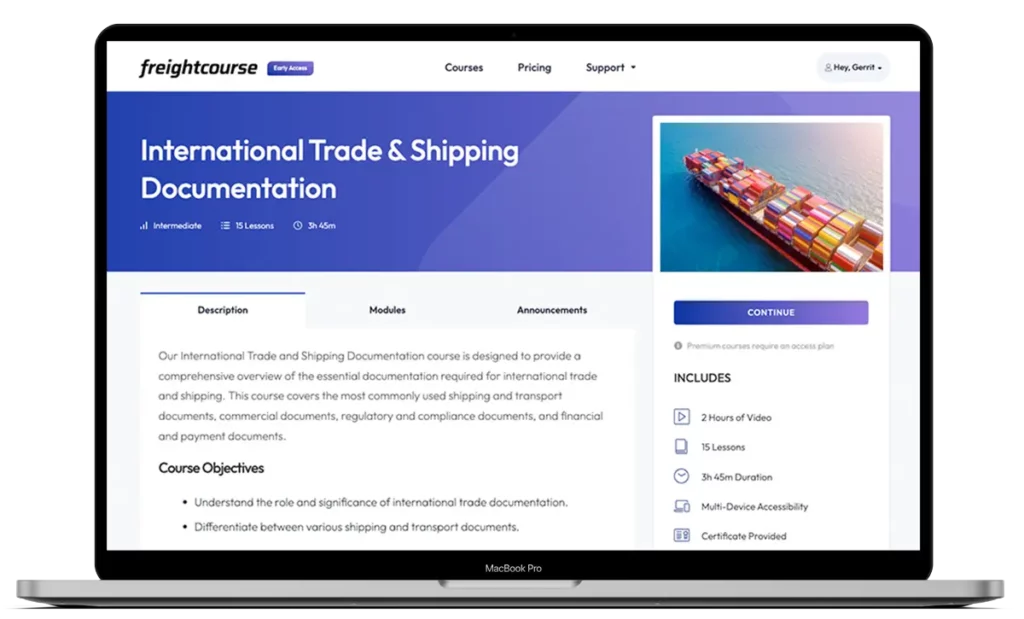

Get Free Course Access

If you enjoyed the article, don’t miss out on our free supply chain courses that help you stay ahead in your industry.

Gerrit Poel

Co-Founder & Writer

at freightcourse

About the Author

Gerrit is a certified international supply chain management professional with 16 years of industry experience, having worked for one of the largest global freight forwarders.

As the co-founder of freightcourse, he’s committed to his passion for serving as a source of education and information on various supply chain topics.

Follow us