To stay competitive, carriers need to adjust their ocean freight pricing strategies frequently. They need to ensure that they remain profitable, especially since some of their costs are variable and can often fluctuate.

As some of these costs are influenced by external market forces, carriers work around this by passing some of these costs to their customers. Therefore, costs such as bunker fuel or currency conversions are often only valid at the time of shipping compared to freight rates that typically have a longer validity.

VATOS stands for “Variable Charges at the Time of Shipment” and means that the variable charges that a carrier has quoted (such as BAF, CAF, or GRI) are subject to the time the cargo is shipped.

This helps protect carriers against cost fluctuations and ensure that they can pass them on to the customer as effectively and as accurately as possible.

What Charges Does VATOS Typically Apply To?

Carriers typically charge variable costs back to the customer at the time of shipping. These costs are usually the Bunker Adjustment Factor (BAF), Currency Adjustment Factor (CAF), General Rate Increase (GRI), and Peak Season Surcharge (PSS). Let’s take a closer look at what these costs are, how carriers deal with these costs, and why they are passed on.

- BAF – Bunker fuel is used to power the engines of an ocean vessel. Like any other fuel, marine fuel tends to fluctuate in price because of supply and demand. Carriers protect themselves by setting a Bunker Adjustment Factor (BAF) that they charge to their customers.

- CAF – Ocean freight charges are typically paid in US dollars, as it remains the backbone of the global economy. As currency pairs fluctuate carriers protect themselves by establishing a currency adjustment factor, that typically represents a percentage of the overall ocean freight costs.

- GRI – General rate increases occur when shipping lines increase the freight rates due to various external and internal factors including changes in market conditions, increases in market rates, or rising operational costs. These rate increases are typically charged to customers and billed at the time of shipping.

- PSS – Carriers charge a peak season surcharge when there is a high demand and low supply for particular trade routes. This rate increase is levied to offset the increase in market rates and is either paid by the shipper or the consignee.

How Is VATOS Calculated?

When looking at a quotation from a carrier, you’ll either notice a VATOS term at the bottom of the quotation or in the terms and conditions. While carriers have their own calculations, the variable charges often apply “at the time of shipping”.

This either means when the container is loaded onto the vessel, or when the container has been shipped (in other words, when the vessel has departed). For example, when a carrier determines variable rates, like CAF or BAF, and fixes them on a monthly basis, the rate that applies to that shipment then depends on which month the container was shipped.

Case Study: VATOS

Now that we have learned what VATOS means, what variable charges this applies to, and how it’s calculated, let’s take a look at a case study using the following table.

| Month | Ocean Freight | BAF | Total Invoice |

| January | $600.00 | USD 552.00 | USD 1,152.00 |

| February | $600.00 | USD 563.00 | USD 1,163.00 |

| March | $600.00 | USD 584.00 | USD 1,184.00 |

Our example is for shipments from Singapore to the port of Los Angeles, in the United States. Based on the table, you can see that the total ocean freight charge remains constant at USD 600.

In the third column, you’ll be able to see that the BAF fluctuates, as fuel prices rise and fall regularly. This means that all containers that were shipped in January for example, have a BAF charge of USD 552.

This is because a VATOS clause stipulated that the BAF is charged at the time the containers are shipped, and not when the shipment has arrived or the invoice was raised.

Can VATOS Terms Be Negotiated With Carriers?

It’s important to note that carriers generally adhere to industry-standard terms and are often reluctant to remove them. However, there may be room for negotiation regarding the averaging method and frequency of calculating the abovementioned variable charges.

For example, you can discuss whether the charges should be averaged monthly, bi-monthly, annually, weekly, or daily. It’s important to note that increasing the frequency of changes requires additional administrative work for both parties involved.

Here are some more tips that you can consider to reduce the overall impact of high variable charges:

- Time and deliver your shipments before or after the peak season

- Read in detail the carrier’s quotation and terms and conditions

- Review the entire freight invoice and see if certain costs can be reduced

- Maximize container utilization to bring down the total cost of ocean freight

- Request a full breakdown of your invoice to understand each line item charge

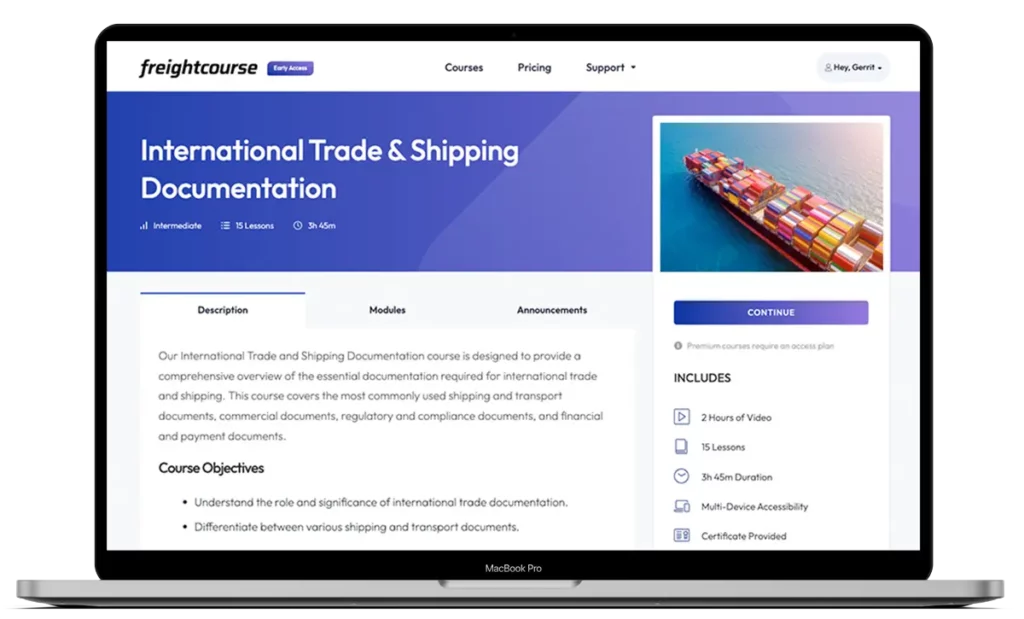

Get Free Course Access

If you enjoyed the article, don’t miss out on our free supply chain courses that help you stay ahead in your industry.

Gerrit Poel

Co-Founder & Writer

at freightcourse

About the Author

Gerrit is a certified international supply chain management professional with 16 years of industry experience, having worked for one of the largest global freight forwarders.

As the co-founder of freightcourse, he’s committed to his passion for serving as a source of education and information on various supply chain topics.

Follow us